Summary: An ambiguous duck rabbit figure shifts visual perceptions for 123 years after a first appearance in a German humorous weekly in October 1892.

An ambiguous duck rabbit figure still shifts visual perceptions as viewers see a duck, a rabbit or both 123 years after its first appearance, captioned as “animals that look alike: rabbit and duck,” in the Oct. 23, 1892, issue of German humorous weekly Fliegende Blätter.

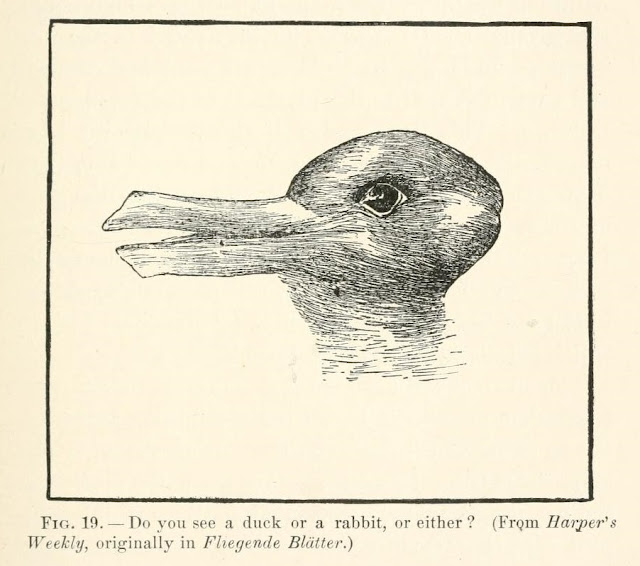

The choice of duck or rabbit is not the main issue in the significance of the ambiguous duck rabbit figure. Although a duck transitions comfortably through air, land and water environments while a rabbit is only a landlubber, both animals lend themselves to sharing the same space, as two images within one image, in the ambiguous duck rabbit figure. The image’s main issue is viewer ability to shift their visual perceptions back and forth between the two animal candidates or to see both duck and rabbit in one glance.

“When it is a rabbit, the face looks to the right and a pair of ears are conspicuous behind; when it is a duck, the face looks to the left and the ears have been changed into the bill,” notes Polish American psychologist Joseph Jastrow in Fact and Fable in Psychology (1900). “Most observers find it difficult to hold either interpretation steadily, the fluctuations being frequent, and coming as a surprise.”

For Jastrow, such ambiguous figures as “the ingenious conceit of the duck-rabbit” reveal the mind’s eye, an interpretative repository of visual images, as a major influence in the physical sense of sight. Jastrow describes ambiguous figures as an “interesting class of illustrations in which a single outward impression changes its character according as it is viewed as representing one thing or another.”

Austrian British philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein differentiates between “seeing” versus “seeing as” in his assessment of the ambiguous duck rabbit figure. The first perception represents object recognition. The switch in identification represents associative identification.

“If you search in a figure (i) for another figure (2), and then find it, you see (i) in a new way. Not only can you give a new kind of description of it, but noticing the second figure was a new visual experience,” explains Wittgenstein.

In a study published 100 years after Fliegende Blätter’s original image, in April 1993, husband-and-wife psychologists Peter and Susanne Brugger find that expectational biases influence visual perceptions of the ambiguous duck rabbit figure at the Zurich Zoo. “The ambiguous drawing, though perceived as a bird by a majority of subjects in October, was most frequently named a bunny on Easter. This biasing effect of expectancy upon perception was observed for young children (2 to 10 years) as well as for older subjects (11 to 93 years),” state the co-authors in the abstract of their study, “The Easter Bunny in October: Is It Disguised as a Duck?”

Twenty-eight days after its introduction by Fliegende Blätter (“Flying Leaves”), the ambiguous duck rabbit figure appears in the Nov. 19, 1892, issue of American political magazine Harper’s Weekly. The bill/ears aspect tilts less upward in Harper’s cartoon than in the original. The greater upward tilt of the bill/ears in Fliegende Blätter’s drawing dramatizes the reversal for viewers who are able to shift back and forth between duck and rabbit perceptions.

|

| Polish American psychologist Joseph Jastrow's ambiguous duck rabbit figure: Fact and Fable in Psychology (1900), p. 295, Public Domain, via Internet Archive |

Twenty-eight days after its introduction by Fliegende Blätter (“Flying Leaves”), the ambiguous duck rabbit figure appears in the Nov. 19, 1892, issue of American political magazine Harper’s Weekly. The bill/ears aspect tilts less upward in Harper’s cartoon than in the original. The greater upward tilt of the bill/ears in Fliegende Blätter’s drawing dramatizes the reversal for viewers who are able to shift back and forth between duck and rabbit perceptions.

Polish American psychologist Joseph Jastrow presents an image in which the bill/ears, eyes and rabbit mouth all share the same plane. Jastrow’s image shares the realism of textured infill with Fliegende Blätter’s and Harper’s Weekly’s versions of the ambiguous duck rabbit figure.

Austrian British philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein offers a stylized image of the ambiguous duck rabbit figure. The bill/ears aspect juts out horizontally from the head and shares the same plane with the rabbit’s mouth. As a stark outline without textured infill, Wittgenstein’s ambiguous duck rabbit figure lacks the realism of preceding images.

As American philosopher of science Thomas Samuel Kuhn notes in his groundbreaking book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), paradigm shifts provoke scientific breakthroughs.

“It is as elementary prototypes for these transformations of the scientist’s world that the familiar demonstrations of a switch in visual gestalt prove so suggestive. What were ducks in the scientist’s world before the revolution are rabbits afterwards.”

|

| Ludwig Wittgenstein's ambiguous duck rabbit figure: Philosophical Investigations (Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret [G.E.M.] Anscombe, trans. 1958), p. 194, Public Domain |

Acknowledgment

My special thanks to talented artists and photographers/concerned organizations who make their fine images available on the internet.

Image credits:

Image credits:

Fliegende Blätter ambiguous duck rabbit figure: Fliegende Blätter, vol. 2465, Oct. 23, 1892, CC BY SA 3.0, via Universität Heidelberg @ http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/fb97/0147?sid=2f4fb9caa7faee86232725383c5bb9b9

Ludwig Wittgenstein's ambiguous duck rabbit figure: Public Domain, @ http://static1.squarespace.com/static/54889e73e4b0a2c1f9891289/t/564b61a4e4b04eca59c4d232/1447780772744/

Joseph Jastrow's ambiguous duck rabbit figure: Fact and Fable in Psychology (1900), p. 295, Public Domain, via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/stream/factfableinpsych01jast#page/295/mode/1up

For further information:

For further information:

BloomsburyPhilosophy @BloomsburyPhilo. "Made famous by Ludwig Wittgenstein, this image is taking the world by storm. . . so what do you see, duck or rabbit?" Twitter. Feb. 17, 2016.

Available @ https://twitter.com/BloomsburyPhilo/status/699954431454916610

Available @ https://twitter.com/BloomsburyPhilo/status/699954431454916610

Brugger, Peter and Susanne. "The Easter bunny in October: is it disguised as a duck?" Perceptual and Motor Skills, vol. 76, no. 2 (April 1993): 577-8.

Available @ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8483671

Available @ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8483671

Farand, Chloe. "Duck or rabbit? The 100-year-old optical illusion that could tell you how creative you are." Independent > News > Science. Feb. 14, 2016.

Available @ http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/duck-or-rabbit-the-100-year-old-optical-illusion-that-tells-you-how-creative-you-are-a6873106.html

Available @ http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/duck-or-rabbit-the-100-year-old-optical-illusion-that-tells-you-how-creative-you-are-a6873106.html

GeoBeats News. "Can You See Two Animals Shown In This Drawing?" YouTube. Feb. 15, 2016.

Available @ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MWNJNLDPJgw

Available @ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MWNJNLDPJgw

Huffadine, Leith. "Can you spot them both? There are TWO animals in this drawing - and psychologists believe what you see says a lot about you." Daily Mail > News. Feb. 13, 2016. Updated Feb. 14, 2016.

Available @ http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3446183/Duck-rabbit-optical-illusion-takes-social-media-storm.html#ixzz40QOURibN

Available @ http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3446183/Duck-rabbit-optical-illusion-takes-social-media-storm.html#ixzz40QOURibN

Jastrow, Joseph. Fact and fable in psychology. London UK: Macmillan and Company, 1901.

Available via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/factfableinpsych01jast

Available via Internet Archive @ https://archive.org/details/factfableinpsych01jast

Kihlstrom, John F. "Joseph Jastrow and His Duck -- Or Is It a Rabbit?" Information Services and Technology Socrates Unix server, University of California, Berkeley > Kihlstrom. Last modified Jan. 20, 2012.

Available @ http://ist-socrates.berkeley.edu/~kihlstrm/JastrowDuck.htm

Available @ http://ist-socrates.berkeley.edu/~kihlstrm/JastrowDuck.htm

Kihlstrom, John F. "A New Reversible Figure and an Old One." University of California, Berkeley, Socrates Unix server > Kihlstrom. Last revised May 25, 2011.

Available @ http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~kihlstrm/SEP06.htm

Available @ http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~kihlstrm/SEP06.htm

Kuhn, Thomas S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Second Edition, enlarged. International Encyclopedia of Unified Science, vol. 2, no. 2. Chicago IL: University of Chicago, 1970.

Available @ http://projektintegracija.pravo.hr/_download/repository/Kuhn_Structure_of_Scientific_Revolutions.pdf

Available @ http://projektintegracija.pravo.hr/_download/repository/Kuhn_Structure_of_Scientific_Revolutions.pdf

Weisstein, Eric W. "Rabbit-Duck Illusion." Wolfram MathWorld.

Available @ http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Rabbit-DuckIllusion.html

Available @ http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Rabbit-DuckIllusion.html

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Philsophical Investigations. Trans. by G.E.M. Anscombe. Oxford UK: Basil Blackwell Ltd., 1958.

Available @ http://static1.squarespace.com/static/54889e73e4b0a2c1f9891289/t/564b61a4e4b04eca59c4d232/1447780772744/

Available @ http://static1.squarespace.com/static/54889e73e4b0a2c1f9891289/t/564b61a4e4b04eca59c4d232/1447780772744/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.